Are we making love or is love making us? Dit zijn de eerste woorden van de lezing die Karin Melis hield gedurende het congres van het Titus Brandsma Instituut in Nijmegen Mysticism on/as love theory. Haar antwoord is onbeslist, maar het is als een dans. Geen theorie. Liefde zal ons immer laten dansen. Lees haar wals hier.

Are we making love? Or is love making us? It’s the eternal recurring question of the dancer and the dance. The answer will always and rightfully so remain a secret. But love will continue to make us love, just as the dance will continue to dance us. So I invite you to tango with Hadewijch’s Seventh Vision, occurring in the midst of her cycle of fourteen visions. The Seventh Vision ís the dance, the voice that leads us to many different places. (Hier is het zevende visioen van Hadewijch te lezen: Hadewijch, Seventh vision)

So.

At the outset of our attempt to understand or interpret Hadewijch’s Seventh Vision I suggest to liberate ourselves from God and especially from all our modelling of and building arguments on him. It will free God himself too. Love happening is a mystic experience and in the interpretation I am offering you, I take The Seventh Vision exemplary for this: it’s happening in this world, but it is not part of our worldly, western affairs which are highly dominated by our intellect’s control. Hearing Hadewijch’s Seventh Vision we are in no need for building our theological or philosophical cases. For a mystic experience of love happening cannot be captured or appropriated in any intellectual way; worse, intellect´s control will certainly destroy love, for such is the power of the language of theory. Psychiatry´s handbook DSM-5 most probably will classify Hadewijch´s account as a not-understandable delusional disorder, reducing it to a distortion of the psyche. Yet, it is precisely the resistance of any identification, which makes a mystic experience what it is: disrupting everything we think or believe to know. Stammering is the most we are capable of when we are overcome by love happening, a mystic experience, this glorious moment of our bodily soul, our soulful body. So that is why love invents and reinvents itself, to paraphrase Rimbaud, in desperate necessity to happen over and over again to no end.

It´s an achievement, I would say an honorable justification, this labeling of mysticism as heresy; a misfit to scholars, scholarly thinking leaning/depending on dogma’s, not much unlike the church´s doctrine´s. Disruptive as a mystical experience is, it leaves every system, order or structure powerless being unmasked as just a system, just an order and just a structure, being just one way of being among many other different forms and instances in this world. What we held for irrefutable is undone of its absoluteness, which was and still is good enough reason for abandoning mystical experiences as being heresy. This rejection only affirms the fundamental weakness of an institution. Even language, things named, is bending backwards in its limitations. Mystics are known for their struggle to put their disruptive experiences in testimonials. Identification by words, or even worse by concepts, brings forth frustration, because a mystical experience cannot be reduced to this, that or any order. It is precisely out of order. And cannot be possessed nor appropriated, making it one’s own. One needs to be a poet – or a great storyteller – to show things which cannot be presented in ordinary, everyday speech. Language itself needs to disrupt, showing its own limits since, of course, a mystical experience feels most at home in the realm/domain of speechlessness – that’s where it comes into being very much like a spring giving birth to a river. Now, while using the narrative of a vision, using words creating images, Hadewijch does precisely this: she shows, makes us hear speechlessness.

So.

What needs to disrupt, what needs to be unveiled without being resolved? In his tragedies the Greek playwright Euripides is a master in unmasking the (moral) order by which we abide as if it is a law of nature beyond question. He shows how this order is a manmade order, a texture of agreements woven by mortals. And thus thoroughly prone to human destruction. Filled with revenge Medea murders her children, robbing her husband of his immortality. And in another tragedy Hecuba transforms into a dog after her devoted faith in humanness is tested and mortified. It is as if Euripides wants to say: look, the way we relate towards each other are governed by human agreements, they are not some sort of fixed orders written in the solar system or written in stone for that matter. Yet Euripides refuses to give a solution, he doesn’t step into the pitfall creating new universal, irrefutable rules and orders. He knows: they too will be just rules, just orders. One may wonder, maybe they are just called into being in order to be tested to bring or rather bounce us back home – if only for a while, before we are once again confined to our old paltry state. By back home, I don’t mean some sort of obscure origin, but, I dare to say, a more realistic, yes, more real source. Namely, our own body, our supreme source of existential knowledge which we tend to ignore or even belittle when it comes down to its insights without which we really cannot do. The intellect is smart in developing mathematical constructs. Or in discovering and applying rational cause and effect as a firm grid covering – and controlling – every thinkable field of our existence under the sun, indeed as if written in stone or the solar system, but what good does that bring while living our fundamental reckless and unpredictable lives in this world? Is our intellect fit to apprehend a mystical experience?

Of course, I should not speak of mystical experiences in general terms, making them harmless by harboring them in abstractness, this platonic, bodiless place of misleading comfort. Let me be bold and not be silenced as Wittgenstein silenced himself when he, inspired by phenomena which appear at our horizons as unspeakable otherworldly, declared:“Wovon man nicht sprechen kann, darüber muß man schweigen.” Even when I most certainly will fail to clarify a phenomenon which, so my intuition whispers to me, is a secret wrapped in silence, the attempt will be worthwhile. To marvel in the nearness of a mystical experience is like hosting questions, those uninvited guests who trouble us and keep us awake during the night. Is it a black hole where all matter disappears or, on the contrary, a bright hole? A timeless omnipresence of the soul/spirit? Or is this mystical experience maybe more real than our surrounding everyday realm which for a moment is put into question? What is it that’s on the line here? Our life, our heart, our soul?

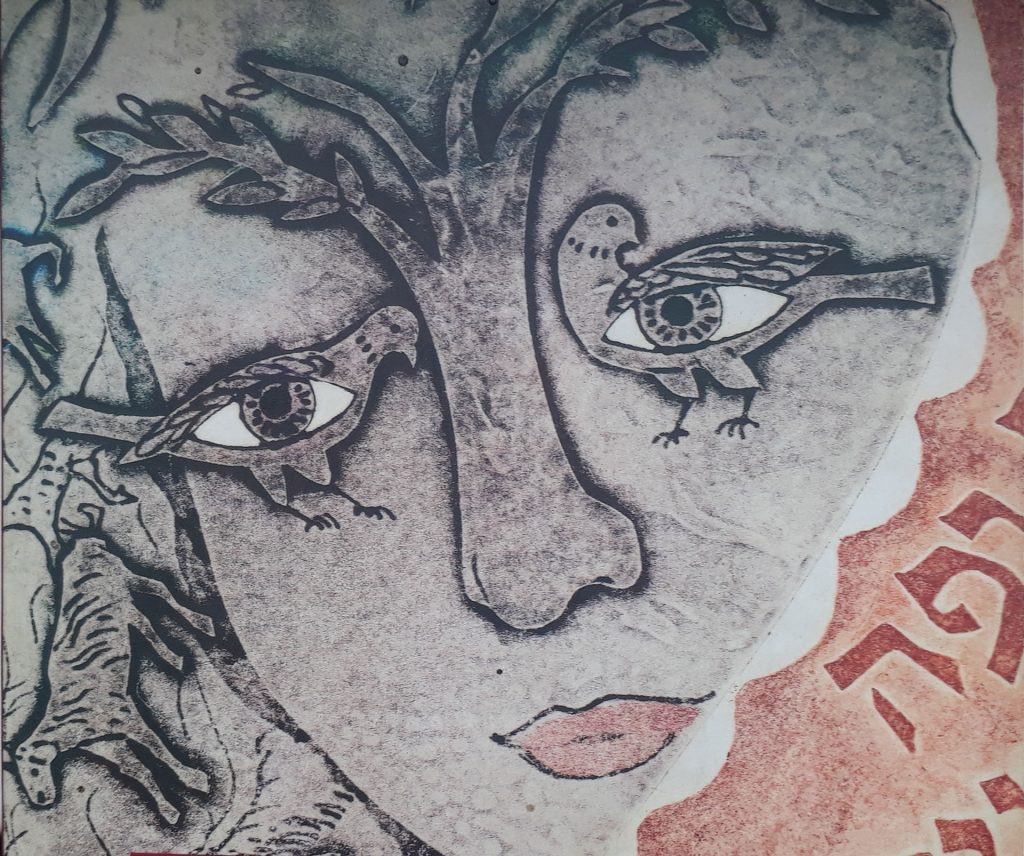

The Seventh Vision of Hadewijch is a highly personal, sensual testimony of a mystical experience. This mystic lady is recounting an experience of love happening — using the narrative of a vision. The interior of a church is the stage, there is an altar and somewhere a large eagle must be sitting on the altar; this eagle has a voice, he has words. And there is Hadewijch herself, of course, who is inward physically burning of passion and desire (orewoet) when we enter the story. It is Pentecost, at the break of day. Hadewijch is praying matins when her inner turmoil – exhaustion by the terrible depth of my passion – hits rock-bottom. In her Vision she testifies how indescribable her desire is. There are no words, she says, to express what she feels, nor people to understand them: “(….)What I have to say about it would not be comprehensible to anyone who has not experienced the effects of love or whom love has passed by.” We picture Hadewijch, a woman living in the 13th century widely known as a spiritual and intellectual authority to many of her sisters, a woman who now during praying, is inwardly bent over in suffering of this burning passion and desire for the one she loves: I longed to receive my love deeply, to know him through and through. Later, when she sits down to make us readers intimate witnesses of love overcoming her, she reflects on how one must allow this suffering, this ‘untold sorrow’ without yielding to it. Always, she teaches in retrospect, feel nothing else than ‘magnificent love, embracing and kisses’. Endure the desire. But this observation comes later, after the event. Now, at this moment, she is praying matins while overpowered by this ‘untold sorrow’.

At this point the large eagle makes himself known. Seeing the unbearable suffering of the woman he is moved and comes flying from the altar towards her, his huge wings spread. (Remember, it’s Pentecost.) Then, as a postilion d’amour the eagle mediates between the lovers, that is, between the one who is present and the absence of the one whom is desperately longed for. It is here that Hadewijch’s vision gets more and more filled with images as if to give proof of the realness of her experience. As she stresses: “All this was real, visible, palpable and testable – just as one really tastes the sacrament and visible and palpable as lovers who are lost in each other in the pleasure of seeing and hearing.”

Trying to get as close to reality as possible Hadewijch vividly describes the play of appearing, she sees her lover literally come into being an adult man of great charm and beauty. She describes the intimate closeness to the skin and finally the disappearance of the lovers in unity:

“Then he approached close to me, took me

completely in his arms, and pressed me to him. All my

limbs felt his to their total satisfaction, as my human heart

desired. Likewise, I had just the strength to bear this, but all

too soon I began to lose sight of the so wonderfully

handsome man, and I saw him fading and melting away till

I could no longer perceive him near me, and with me I

could not distinguish him from myself. At that moment I

had the feeling we were one together, without

distinction.”

In some ways this remarkable account is reminiscent to the Song of Songs, that endless song of longing to bridge the ravine between absence and presence. The poet of the Song of Songs uses colorful images to present the burning passion and desire of the two lovers involved. Yet, while using these images, the Song of Songs gives room to more innocent/metaphoric interpretations, that is: in some prominent religious area’s more fit to the church doctrine.

When spirituality or, for that matter, mysticism is put in general and thus accessible terms, it loses its edge, its radical difference. I prefer to speak of a mystical experience because it is highly subjective and by consequence not to be generalized. yes

What gets under my skin while reading the Seventh Vision of Hadewijch is that here the recounting is in the first person: it is all happening to the mystic Hadewijch herself and she is telling it us, readers, transforming us in intimate witnesses. This vision is remarkable because Hadewijch is straightforward in her sensual descriptions of how love and longing make themselves known in her body and how her body grows to know him through and through while fusing with one and another. Of course, for her the body is the materialization of the soul/spirit. When she recounts of love happening, she is attuned to the First Testament, more precise to the Hebrew: though body and soul are different, they are inseparable aspects of oneness: man/woman is soul, living being, as man/woman is also flesh. The flesh, our body, doesn’t come into being without the soul, our breath. The soul does not coincide with the body, the soul makes itself known through the body, it’s her home – she depends on the body and vice versa.

Even though Hadewijch’s account might seem thoroughly erotic or even sexual in our ears, for her, without dismissing the sensuality, love happening is throughout spiritual, or should I say, soulful? – finding its beginning and ending (the alpha and omega) however in the flesh. Her body, the temple of her soul, brings her knowledge, that is: loving is knowing, knowing is loving – ‘I longed to receive my love deeply, to know him through and through’. But this knowing is not a knowing as we generally understand it in terms of identification. It is not a knowing deduced from a perception in time and space even though it does take place within the spatial-time dimension. Hadewijch’s experience in the church while praying the matins, her desire which brought her bones almost to the point of breaking, the mediation of the large and all-knowing/seeing eagle, the sensual encounter orgasmic climaxing in the disappearance of the lovers in unity, all these events overcoming her took place in time and space but the experience itself withdrew itself from these dimensions. I wouldn’t be surprised if everything, every movement of the story of the vision, was all there at once, a blink of the eye, overthrowing everything that was present in the outer world surrounding her.

Relentlessly we are in search for a locus where we can secure/place the things of life. However, a mystical experience as is described in The Seventh Vision (and I would argue any other mystic experience) resists any categorization, identification — any attempt to psychologically explain this experience is a violation of the event itself because it reduces the encompassing sensation which embraced the lovers. This event of love happening, as I call it, takes place within human existence but cannot be captured within a form or convention which may leave the person involved powerless, for that is what we generally do: we identify and thus empower ourselves by fixating our experiences so as to safeguard our organized lives, including our inward state of being. Not so by Hadewijch.

The bodily sensations – the desire, the longing, the melting away in unity with the other – inspire Hadewijch’s mystical experience throughout. She never questions what her body is telling, what it makes known to her, in fact, one could argue that Hadewijch is thoroughly her body occupying every blood vessel, every bone that is at the point of breaking, stated as in a figure of speech: she feels her hair growing. Her soul is her body and vice versa. And she is taking it dead serious, there is nothing in this proud mystic that will rationalize this experience abandoning it safely to the land of the unknown or worse to the condemnation of irrationality or emotionality which are just different ways of eliminating what doesn’t fit in the modern, scientific grid (a form of heresy…). Observing a mystic experience like Hadewijch’s with ‘2.0 eyes’, one is confronted with the present dominance of instrumental reason which has alienated us from ourselves as mortal, bodily souls.

What if Hadewijch didn’t have a sensual, all fulfilling encounter wherein all her limbs felt his in total satisfaction? What if the meeting with her lover was one without touching and embracing, was, in short, thoroughly transcendent? Completely detached from the body, like a bodiless spirit. Contrary to Hadewijch´s Seventh Vision where the feverish flesh unites the lovers´ soul, i.e. being. I envision the radical detachment from the body being a kind of shortcut where the physical weight of the flesh is escaped in relief – if only for a brief moment. Now the body appears as a prison of the soul instead of a temple. Life forsaken are words that pops to mind. Forsaking the earth, the creation of our physical existence, that what is given to us. Without rejecting the worth of a contemplative, meditative way of being, I like to raise the rhetorical question here what would the meaning of The Seventh Vision be without this sexual inspired fusion in love happening?

Love, minne, is the key of Hadewijch’s life and being. In order to turn this key we are in need for the words of a poet. ‘Love is a thinking,’ says the Portuguese poet Pessoa – the French philosopher Alain Badiou quotes him favorably. A thinking of love, i.e. the body? Does our body think or does our flesh fully come to the fore when the mind, that is our modern rationale, our instrument to model/control the world and ourselves, is silenced? Is this how we may understand Leskly’s poetic words:

When the word becomes flesh

and the body opens its mouth

and when it speaks the word from which it is created

I will embrace that body.

Badiou is worried about the current state of love. He observes how love has become a project executed in dating-sites summing up our desires/criteria which our future lovers have to live up to. Baidou speaks of how risk avoiding we have become when we enter the arena of love, or, more to the point, when love enters our arena. What kind of risk? In everyday life, we are in need of a health-insurance so we are taken care of in case health deserts us or when we are otherwise wounded. We insure are houses, our global trips and we have cancellation insurances in case the trips don’t come through. We insure ourselves against risks or at least we are in need for (financial) compensations when risks hit us. Really, what is the risk we believe we are exposed to, what do we really want to insure, while simultaneously we love to explore adventurous unfamiliar places the world has to offer us. Is a meaningful, satisfactory life a life that knows how to effectively fend off risks? What is it that we want to be immune for? Maybe we are afraid to get hurt. But what is the pain we are afraid to suffer? The pain of a derailed life, homelessness, losing our loved ones, losing ourselves, to be unknown, never to be fully known, to be unmasked or finally laid bare in loving arms? But now what?

Badiou receives love as full of risk because it is then when we are really at stake. Being loved we are known in a way, we cannot capture with our intellect, we just can’t fathom it, our tongue is lame. In fact, our intellect is empty handed. It’s incapable to address: ah, so that’s me. There is no identification here we can built politics upon or some other operation in the hope of deserving ‘likes’. Distinctions are not in the doing here, if anything there is dissolution and still there is this encompassing being known and received. Hadewijch describes how she herself and the handsome man melted away, disappearing in fusion. ‘There was naught of me left,’ the mystic says. And yet Hadewijch encourages us to stay with ‘love magnificent, embraces, kisses’. And not to yield to ‘untold sorrow’, absence, desire. Being known, that is loved, calls forth a complete being there, ripped off are the skins of shame, shyness, incompleteness. Yes, ripped off, but here (a) secret is laid bare. A secret which cannot be unveiled despite that tantrum of our intellect which wants nothing more than to reveal, to explain, to master, to control, et cetera.

So. One day Hadewijch sits down at her table. All this time the mystic has been trying in avail and, it must be said, against better judgement, to integrate her unheard-of-experience, her suffering by passion and desire, her praying, her aching body, the eagle flying from the altar, talking, begging and praying, the orgasmic fusion with the one she loves beyond any understanding, in her life as a devoted and intellectual woman. All this time Hadewijch mourned the absence of her lover. He disappeared in their fusion showing her many different times. She is left by herself in her ordinary life, yet, never in her life did she stop looking for signs, traces, a face just in passing turning the corner of a street. From the outside nothing had changed, inside nothing is the same. Hadewijch knows: she can’t incorporate this, shouldn’t do so either for she would lose love. The inability to share her mystic experience with her sisters is nevertheless overwhelming, she doesn’t have words, there is no story to tell, the tears as well as the immense joy seem to be all in one – indivisible as pain is. Reliving her experience endlessly so as to inspire and strengthen her innermost being, she gradually discerns what she begins to call the ‘untold sorrow’. Now she grows in determination: She will not yield to that sorrow darkening the encompassing love she has experienced (and still experiences) in the lonely, isolated times in which she again and again disappears in ‘many different times’.

But now, she wants to put her mystic experience into writing, using vernacular language and the narrative of a vision. The mystic wants to safe what had happened to her that morning of Pentecost. Now, this lady is gifted, she is literary eloquent. She knows how to tell a story. Hadewijch is also candid, frank, doesn´t hold back. By now, sitting at that table she is fully aware that she is unable to unravel the secret that is carrying her existence as soil. The secret must remain a secret simply because it is a secret. And so she is on the road, circumscribing the suffering of her desire, the untold sorrow. There he is, the eagle, talking to her, pleading for her to the lover to unite with her, to love her. She takes the road from her inner turmoil, carried away by the voice of the eagle towards the loving encounter. And this encounter, the centerpiece of her life, her being, is wrapped in complete silence. Despite the description of lovers who are lost in each other in the pleasure of seeing and hearing, there is no voice to be heard, no words spoken.

Woorden van

Karin Melis

Gepubliceerd op

Geplaatst in

Lees hierna

Dit zijn woorden van

Karin Melis

Onafhankelijke filosoof en publicist.