Gevlucht. Hoe maak je het onzichtbare zichtbaar?

Zij is docent Franse literatuur, hij is goudsmid. Ze hebben twee kinderen. In het weekend gaan ze naar hun buitenhuis. Dat was daar en toen. In Syrië. Inmiddels hebben Ranya en Nedal drie kinderen en wonen sinds een slordige vier jaar in Huizen. Vorig jaar zomer volgde verhalenfotograaf Annelies van ’t Hul deze Syrische vluchtelingen op de voet. Een schier onmogelijke opgave, want hoe maak je onzichtbaarheid zichtbaar? De onzichtbaarheid van verlies van identiteit, van geliefden achtergebleven in oorlogsgebied, van de sociale ontreddering als het maken van contact zo moeilijk is? Fotografe Annelies van ´t Hul deed het. Karin Melis schreef het verhaal.

Refugee Faced

Rebuilding identity in asylum

When Ranya (35), teacher in French literature, mother of three children, tries to grasp the diagnosis of her blurring eyesight in the hospital ‘de Zonnestraal’ all fences fall. It is one of the rare moments in this intimate portrait of the members of a Syrian family who were forced to leave their country for their own safety, that the hidden background comes to the fore. Ranya calls her family in her mother tongue: Arab. In this dramatic moment the loss of familiar bounds are all too obvious and painful. For months photographer Annelies van ‘t Hul followed the footsteps of Ranya and her family in their attempts to find their way in The Netherlands. Time and again they are facing the invisibility of their original belonging in Syria. At one point Ranya says: “We are paying for the Syrian war.” They were driven from their home and their safety nets. Yet, in their struggle to find a place in a world that is not their own, there are lights giving them hope for the next day. Annelies reconstructs the way in which Ranya and her family try to become visible in a world that doesn’t know them and whom they do not know. The photographer walks the tragic line between the invisible and the visible. It’s not always what it seems to be.

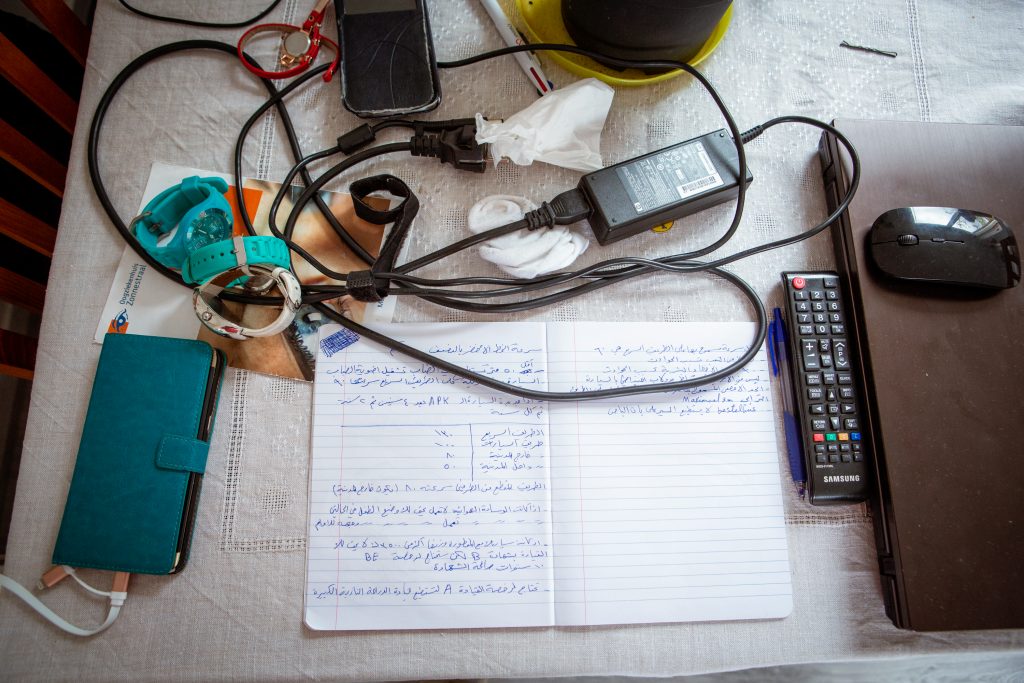

Ranya is taking notes while studying for the theoretical exam of the Dutch drivers-license. Luckily she can do this in Arab. Studying in Dutch is too difficult for her to concentrate on, while her three energetic children are around her in the same living room all day during the summer holidays. Her cellphone is never out of reach, as she regularly uses message service to stay in contact with her family abroad. A leaflet from the eye-clinic ‘Zonnestraal’ is still left on the table after her recent visit to the doctor.

Since a while now her eyesight is blurred, sometimes there are blots, distancing herself from her surroundings. It makes her anxious. She has no idea what´s going on, let alone what to do, she needs an expert, a doctor. Here the thinking stops: How do you explain a loss of clarity in the eye in Dutch? What will happen when it’s serious, how can she take care of her three children, cook, in short, live? She will never be able to go to a Dutch university to validate her Syrian degree in French literature. God knows how much she yearns teaching again, albeit, in a Dutch classroom. Her Dutch is getting better every day. She already has her certificate in Dutch as second language and, God knows, she is proud of it. However, writing is an altogether different and harder issue to tackle. She is aware of this, but she will work on it relentlessly. If she would lose the light in her eyes, it would all end right here in the social housing in Huizen, living upstairs with her husband Nedal and their three children.

Her youngest 2-year old son Pieter doesn’t understand why his mother is upset and talking on the phone in Arab. Ranya uses the highchair to make sure he can’t move around, while she has to share her thoughts and feelings after being diagnosed with cataract, far too young for her age.

Ranya suppresses the fond memories of the weekends they spent in their place in the country, fleeing from the dust and work in Aleppo. This place, so dear to the heart, surrounded by numerous trees bearing all kinds of fruit, has been taken by the IS. It’s theirs no more. But now they are here. She must focus on the loveliness of The Netherlands. She just adores its greenness. Trees everywhere and everything is so neat and organized. It makes her feel grateful that this country has opened its arms to receive them, even though, she has to admit, it turned out so much harder than she could have imagined. Take the endless paperwork because of inscrutable rules which, she is sure, she will never understand, let alone make them her own. A land of paper, that’s what Nedal calls The Netherlands sometimes.

She recalls how Nedal was on the phone with the electricity-company Qurrent. Their contract was due for extension. The lady on the phone, Ranya could hear her voice, the speaker of his cellphone was on, spoke too fast. There were technical details about energy rates which included delivery costs, the lady babbled on and on. She could tell from the bending of his voice that her husband could not catch up. Finally, the lady and he agreed to talk again later in the year in order to finalize the extension of the contract.

While preparing food in assignment for the catering cooperation, though unpaid except for a compensation for her expenses, Ranya stares out of her kitchen window. A few years ago her sight from her kitchen window in Aleppo was totally different. She should not think about that too much. Those days are gone. In the living room Pieter balances between focussing on the television and screaming for attention of his mother. Ranya can ignore his endless whining for attention to some extend, but as soon as he gets too loud she has to intervene not to disturb her neighbors too much.

There is always this lingering despair not to be understood. Missing the adequate words, which makes Ranya feel silly, her being so talented in the linguistics back home. It’s awkward, at times she needs to rely on the Dutch linguistic skills of her 10-year old daughter. But, she speaks sternly now to herself, one should never turn his back to the generosity of acceptance of their host land. They named their third child Pieter, in honor of The Netherlands. After all, he was born here after she and their Syrian born kids Estephany and George (5) were reunited on Dutch grounds. For them Pieter is a sign of hope for a beckoning future perspective after the Syrian war had destroyed their lives.

Every afternoon a moment of silence arises as soon as Pieter is taking his daily nap on the coach, under the wakening eyes of the religious objects, showing their Catholic faith. This toddler seems to have an on-/off button. Once he is awake, you definitely will know he is around. It is in these small windows of napping time that Ranya can do some necessary tasks, without her having to keep an eye on Pieter all the time.

Nedal fled the Syrian war in 2014, leaving his bombed and plundered shop which he ran as goldsmith together with his six employees. Leaving Ranya and their two kids, in search for a future homeland to rebuilt their lives in safety. Nedal and Ranya knew that The Netherlands allowed families to be reunited within one year, the main reason they winded up here. It was a long road he travelled with a modest rucksack. Only dressed in shorts, a casual polo-shirt and loafers on his feet, he looked like an innocent tourist. Via Lebanon, he arrived in Turkey taking a boat to Greece. From there he boarded for a flight to Amsterdam and went directly to the police. Ter Apel was the first of eight asylum seekers centers he stayed at. All the while they were separated Ranya found herself surrounded by the sound of war without electricity, gas and water. There was no milk for the children. All this suffering along with the struggle to survive and find a safe haven for their family, Ranya realizes all too well that the people they meet in The Netherlands can´t see this hidden context. In fact, they appear as an ordinary family living in Huizen. It´s only when they make an attempt to communicate that people grasp they are not from here. It’s then that they appear as Syrian refugees eager to establish their lives.

In this atelier Nedal practices his profession as a goldsmith, though unpaid. At the same time he learns related skills, whereas the jewellery industry in The Netherlands differs quite a lot from the one in Syria.

Going to church on Sunday, being there amidst others, praying to their common God resolves all misunderstanding they endure during the week. Faith is their source of strength. It is in church that Nedal and Ranya met Frans. Honestly, this man is Godsend. Frans, already 80, helps them with practical stuff, mediates in conversations with officials and their forms they find so hard to decipher. It was Frans who helped Nedal to formulate his curriculum vitae in Dutch. In search for work the two men visited jewelry stores. It was hard, the differences are great. Here in The Netherlands silver is much more common than in Syria where gold and its mass production in jewelry was the dominant business. Equally, Ranya was surprised to discover that French lessons here are taught with Dutch textbooks, whereas in Syria they exclusively spoke French using French textbooks. Nevertheless, they are grateful that Nedal found an internship for one day a week at the store of Natalie Hoogeveen, a jewelry smith. Of course, it is unpaid, but at least Nedal enjoys practicing his profession. Shortly this will end, because Nedal is summoned by the officials here in Huizen to find a job soon, maybe not his level, maybe something completely different.

Ranya herself is busy with, and this is hard to admit, exhausted by taking care of their three energetic kids. Yet, she has managed to start cooking by assignment for a cooperation. Working with other women, is joyful. That´s how she lived in Syria, working together. Above all, cooking is her lust for life. It doesn’t matter where they serve the Syrian food Ranya prepared in her kitchen. Recently, they were serving out in a chic district for the Rotary Club. She felt self-assured and thrilled, enthusiastically explaining their dishes This she painfully lacks in everyday life here in The Netherlands. It is as if she is hitting the wrong chord and as a result a part of herself disappears underground.

A huge contrast with their own residence is tangible when Ranya and her colleague are unloading the car with their Syran dishes in a chic district with huge villas, wide lanes, lots of beautiful old trees and gardens as big as a soccer pitch. Nevertheless at these moments she feels self-assured and thrilled, showing almost a different lady than the exhausted mother of three.

Speaking of hitting the wrong chord, there is this painful ongoing issue going on with her neighbor. During the summer the woman had filed a complaint at the police because her children were too loud. Policemen were standing here in the living room. They turned out to be really nice finding nothing wrong with her family. Indeed, they were an ordinary family with three kids. Ranya invited the woman so the two of them could talk it over, but she never responded to the invitation. Social life in The Netherlands is puzzling to her. It is hard to make friends. She really misses all her dear ones back home where she was appreciated for who she is. Here the social code is indecipherable. At least for them. Still, she cherishes their achievements. Nedal already has a Dutch drivers-license. Ranya herself accomplished the theoretical part of the drivers-license. It helped that she could do this in Arab. Luckily Estephany didn’t need any language to pass her Dutch swimming-diploma. Now Ranya is searching for an instructor to teach her driving on the Dutch streets and highways.

There will be no driving for her when the blurs and blots keep hindering her eyesight. It frightens her. Ranya and Nedal visited the eye-doctor in the eye-clinic ‘Zonnestraal’ in Hilversum. It all went by so quick, too bad that Frans couldn’t come this time, the doctor talked so fast. Before they knew it, they were standing outside. There was a lady who patiently explained to them that she was suffering, far too young for her age, from cataract. It was only in a beginning stage. There would be too many complications for surgery right now. Maybe in ten years. By now her mind too seemed to be blurring. At home Ranya takes her cellphone, she tumbles over words in the mouthpiece. In Arab.

Just before the documentary reached its deadline there was a fortunate turn of events in Ranya’s life. Word spread and landed that Ranya is looking for a teaching-position in French. Accompanied by Annelies she had an introductory meeting with Femke Hagg who mediates in teaching jobs. Just when Annelies wanted to get in her car and leave, her cellphone rang. There might be an opening for Ranja tutoring pupils. For her it is if one of her deepest wishes is coming true since her arrival in The Netherlands.

November 2018

Psychiatrist Pim Scholte: “The case of refugees is a case of social bonds”

We cannot see the reasons why people fled their home country and the trauma’s which subsequently have scarred them. This all remains hidden in the ordinary course of life, bringing the kids to school, taking driving lessons or doing groceries. We don’t know whether a refugee, man or woman, was a doctor or a farmer back home. The group where they belonged to, their former colleagues, family-members and friends, has disappeared and with that their inner sense of belonging. In his TEDxTalk (July, 2016) psychiatrist Pim Scholte explains at length how indispensable social bonds are for our sense of being. Our identity is formed by our surroundings in the broadest sense of the word. As Scholte, who was a board member for twelve years for Doctors without Borders during which he played an initiating and advisory role in mental health programming, puts it plainly: “I am through the other.” This insight has its African roots in Ubuntu: I am, because we are. No wonder Scholte has such a heartfelt insight, the refugee camps in Africa were his working place. Time and again he experienced what happens to people when they are displaced and their familiar context has evaporated. The psychiatrist regards this as the core of the problems around refugees who try to find a home in a foreign country: they lost their role and their social context leaving them with a sense that they are unseen. Scholte translates their silent cry: “I am through you, please connect me.”

Zie hier de volledige fotoreportage ‘Refugee faced’ van Annelies van ’t Hul

Woorden van

Annelies van 't Hul en Karin Melis

Gepubliceerd op

Geplaatst in

Lees hierna

Dit zijn woorden van

Annelies van 't Hul en Karin Melis

Annelies van ´t Hul is verhalenfotograaf, bezoek haar website voor meer verhalen. Karin Melis is filosoof en publicist.

Wat een mooie samenwerking tussen jou en Annelies! Prachtig!!